What's the best strategy when playing HORSE?

TL;DR: If you want to win at HORSE, it’s generally a much better strategy to attempt high percentage shots. It almost never makes sense to shoot crazy half-court shots or behind-the-back shots. As a general rule of thumb, never attempt shots that you can’t shoot at >50%.

HORSE is a popular basketball shooting game. The main choice a HORSE player must make is which spots on the basketball court to attempt shots from. What’s the best strategy to win at HORSE?

Game rules

The version of HORSE I’m analysing here involves two players. In the beginning, it’s Player 1’s turn. The player whose turn it is will be called “C”, and the other player will be called “O”.

- C picks a spot on the basketball court and attempts a shot.

- If C misses the shot, it is O’s turn, and we go back to 1.

- If C makes the shot, O must now attempt the same shot.

- If O makes the shot, C’s turn continues, and we go back to 1.

- If O misses the shot, they get a letter. C’s turn continues, and we go back to 1.

- Once any player has gotten 5 letters, ie HORSE, they lose the game.

On Player 2’s turn, Player 1 has no real strategy - they must simply try their best to make the shots that Player 2 makes. The only strategy a player can control is which shots they attempt when it’s their turn.

Expected number of turns

Deriving the formula

Let us calculate the optimal shot on Player 1’s turn. Note that a “turn” lasts as long as the player whose turn it is does not miss their shot. We will assume that Player 1 will shoot the same optimal shot each time it is their turn. Let \(p_1\) be the probability that Player 1 makes this shot, \(p_2\) be the probability that Player 2 makes the same shot, and \(e_N\) be the expected number of turns for Player 1 to win \(N\) letters.

If Player 1 misses the shot, the expected number of turns going forward is \(1 + e_N\), since Player 1 has used up the current turn, and must restart in the same position next turn. If Player 1 makes the shot, and Player 2 misses the shot, the expected number of turns is \(e_{N-1}\), since the turn continues with one less letter to win. Finally, if Player 1 and Player 2 both make the shot, the expected number of turns is simply \(e_N\). Putting these together, we have

\[\begin{equation} e_N = (1 - p_1) (1 + e_N) + p_1 (1 - p_2) e_{N - 1} + p_1 p_2 e_N \end{equation}\]Re-arranging and expanding for \(e_{N-1},e_{N-2}\ldots e_0\), we get

\[\begin{eqnarray} e_N - e_{N - 1} &= \frac{1 - p_1}{p_1 (1 - p_2)} \\ \vdots \\ e_1 - e_0 &= \frac{1 - p_1}{p_1 (1 - p_2)} \end{eqnarray}\]\(e_0\) must be \(1\), since \(p_1=1, p_2=0 \implies e_1=1\). Adding the equations above and re-arranging, we get

\[e_N = 1 + N\frac{1 - p_1}{p_1 (1 - p_2)}\]For the game of HORSE, \(N=5\), and so the expected number of turns to win HORSE is

\[e_5 = 1 + 5\frac{1 - p_1}{p_1 (1 - p_2)} \tag{1} \label{eq:one}\]Our goal is to minimize \(e_5\). \(e_5\) increases with the inverse of the quantities \(\frac{p_1}{1 - p_1}\) and \((1 - p_2)\). Since the former grows much faster than the latter, we can intuit that increasing \(p_1\) is a lot more important than decreasing \(p_2\).

Visualizing the expected number of turns

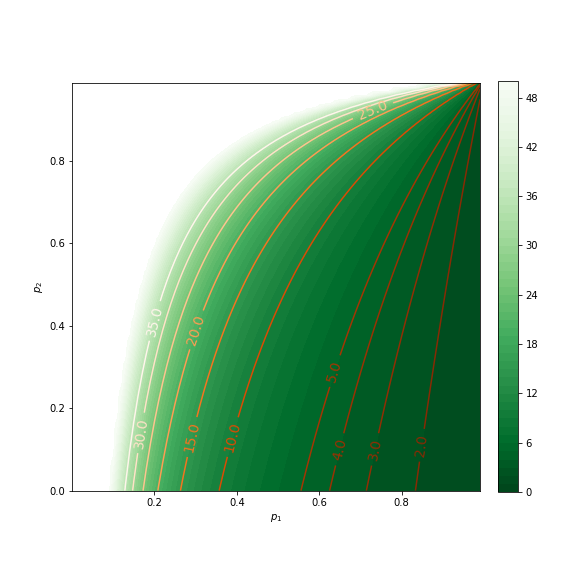

Since this is a function of two variables, we can visualize it with a contour plot.

As the color gets darker, the expected number of turns decreases, ie we’re more likely to win. As we would expect, the plot gets darker for higher values of \(p_1\) and lower values of \(p_2\), ie to the right and bottom of the plot. What’s interesting to note is that the contour lines are “squeezed” more toward the right than the bottom, indicating that a high \(p_1\) has a stronger effect than a low \(p_2\). For example, if \(p_2=0\) and \(p_1=0.2\), \(\eqref{eq:one}\) gives us \(e_5=21\), whereas if \(p_1=1\) and \(p_2=0.8\) we get \(e_5=1\).

Verification via simulation

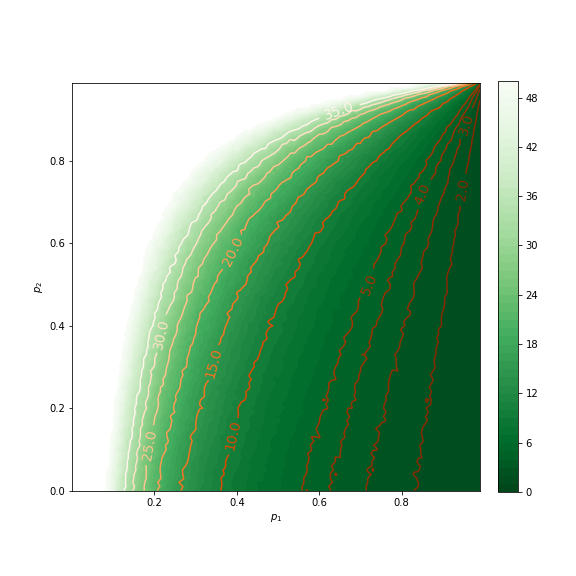

Another way to calculate \(e_5\) empirically is to simulate \(G\) games for each value of \(p_1\) and \(p_2\), and then average the number of turns the game takes to finish over all the games. Doing this with \(G=1000\), I get this plot:

which matches the previous plot. The squiggles are due to randomness.

Analyzing some special cases

In reality, \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) tend to be related to one another, since shots that are harder for one player tend to be harder for the other player as well.

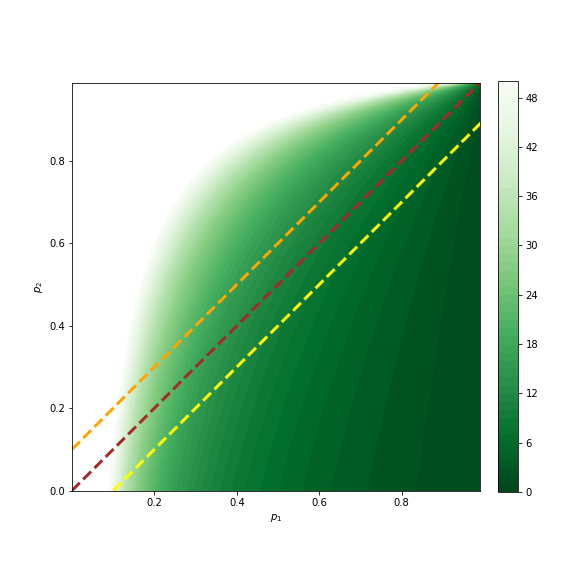

Let us analyse some special cases, corresponding to the straight lines in the following plot.

Both players are equally good shooters

This corresponds to the red line above. Here, \(p_1 = p_2\), and \(\eqref{eq:one}\) simplifies to

\[e_5 = 1 + \frac{5}{p_1}\]To minimize this, we should pick shots with a \(p_1\) as high as possible. For example, if we keep making layups at a probability of \(0.9\) each, we’d expect the game to be over in less than \(7\) turns.

Player 1 is a slightly better shooter than Player 2

Let’s say Player 1 always shoots 10% better than Player 2 for any shot. That is, \(p_2 = min(p_1 - 0.1, 0)\) (yellow line above), and when \(p1>0.1\), \(\eqref{eq:one}\) simplifies to

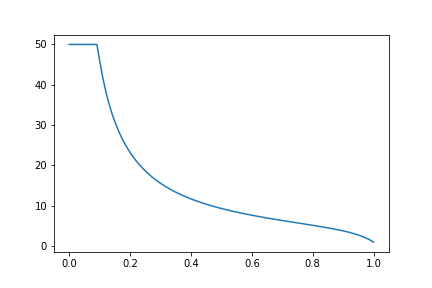

\[e_5 = 1 + 5 \frac{1 - p_1}{p_1 (1.1 - p_1)}\]In the range \(p_1 \in [0, 1]\), this function looks like this:

It is minimized at \(p_1=1\), where \(e_5=1\), that is, the game ends in one turn. Again, Player 1 wants to pick their highest probability shot.

Player 2 is a slightly better shooter than Player 1

Here, we set \(p_2 = p_1 + 0.1\) (orange line above), which gives us for \(p_1 < 0.9\)

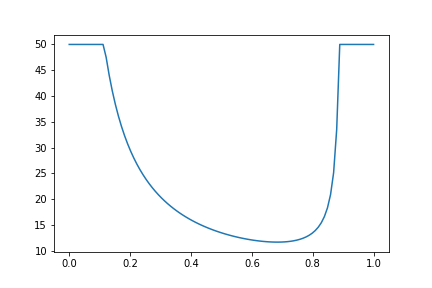

\[e_5 = 1 + 5 \frac{1 - p_1}{p_1 (0.9 - p_1)}\]In the range \(p_1 \in [0, 1]\), this function looks like this:

Interestingly, we cannot simply maximize \(p_1\) here, because once \(p_2\) gets closer to \(1\), we can never win. However, the optimal \(p_1\) is still pretty high, at around \(p_1=0.684\), giving \(e_5=11.7\). If Player 2 (for whom \(e_5\) looks like the previous section) shoots shots at \(p_2<0.4\) (eg three-point shots), they will lose the game, despite being a better shooter.

Real world strategies

In the real world, winning is not the only objective. You don’t want the game to take indefinitely long, and you’d be ridiculed if you kept taking layups. You also have no concrete way to estimate \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) (unless you’ve been playing an opponent for a long time and are keeping a tab on their shooting percentages), and so have to rely on intuition. Some general points to keep in mind:

- You’re generally better off taking high percentage shots, even if you’re much better at a low-percentage shot than an opponent. As an example, let’s say you’ve been practicing half-court shots all year, and you can shoot a half court shot at an impressive 20% (\(p_1=0.2\)). You’re sure your opponent can’t shoot that shot if you make it (\(p_2=0\)). Your expected number of turns to win is still \(e_5=21\). Compare that to you shooting a 60% shot which your opponent can also make at 60% (eg a free throw), which lets you win in \(e_5=9.3\) turns. This is more than twice as good as the half court shot! This is because if you and your opponent both make the shot, it’s still your turn. Whereas if you miss your shot by attempting a low percentage shot, your turn is over. You can always win the game in 6-7 turns simply by taking layups at the same percentage as your opponent (assuming \(p_1\) of 0.8-0.9). If we set \(p_2=0\), and solve for \(e_5=7\), we get \(p_1 = 0.45\). That is, even if your opponent can’t make the shot you make at all, there’s generally no point in taking shots that have \(p_1 < 0.45\) - you’re better off shooting layups.

- If you can guess \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) for a bunch of candidate shots, plug them into \(\eqref{eq:one}\) to figure out which shots are your best bet to win.

- Instead of practicing low percentage shots (like behind the backboard arc shots), practice your high percentage shots (like free throws or left handed layups) instead. If you and your opponent can both make a behind the backboard arc shot at 10%, and you practice to push yourself to 20%, you still go from winning in 51 turns to 23 turns. Compare that with converting your free throw from 60% to 70% - that pushes your expected turns from 9.3 to 6.4.

- Find novel-looking high percentage shots so that you can use an effective strategy while not getting ridiculed for just attempting layups. Examples are left handed close up shots, floaters, bank shots.

I’d also recommend playing HORSE with modified rules, eg

- No shots from inside the paint.

- No repeated shots from the same spot in a turn.

- If both players make three shots in a row, it’s Player 2’s turn.

This should reduce the effectiveness of the layup strategy and make the game more fun.

The code for the plots in this post is here.